If you get a message from your friend, ‘hey what do you think of this idea, I just came up with it real quick’ and then you see they’re typing, and immediately a message two screen-lengths in size appears, about a road trip across the country including very specific stops and what you would do at those locations, you’re going to doubt the ‘real quick’-ness of the idea. As it was when I was communicating this project to people: my message might have sketched some details, but the story paints the picture. The evidence for what a piece of writing is doesn’t lie with an instagram post suggesting what it is, or a book review, or whatever message we may have received from our friend asking if we wanted to read something, it lies with the writing itself. So this gap between communication about the story and the story itself is what I’m referring to when I say ‘comms issues’. There were a few of them. None of them were problems to be fixed, instead they illuminate some things I’ve learnt along the way.

a. the cry list is… fiction? right?

When sharing about this project I merely mentioned the cry list was fiction. But the first chapter, the one where the narrator remembers stories about the other members of their family, caused some readers to do a double take that expressed something akin to (I imagine in any case) ‘wait are you just writing about your real life family?’

So the evidence when you read the cry list (i.e. style of writing, references to journalling, the mundane nature of events in the story, etc.) suggested that this didn’t necessarily have to be fiction, or even if it was, maybe it was largely autobiographical.

But… I don’t have a sister. My family’s various homes have never been like the one in the story. It’s certainly not non-fiction. It’s not autobiographical. Much of the fun of writing this piece was in imagining a family that was in unlike mine. It would not even be correct to say that the family scenarios are some blurry version of my life. The dinner in chapter two, for instance, is wholly unrecognisable to me. Fiction.

Where (if anywhere) does the story resemble my life? There are small ways: tiny scraps of dialogue, a few thoughts I have shared with friends before, imagining a character in one element of a scenario I know someone has been in, being inspired by a few particular songs for some descriptions of music. I wonder how difficult a story would be to write if you could not use anything you had heard or said before.

And then there are two more significant ways the cry list resembles my life.

The narrator has a different set of problems to me, but maybe the ways they would attempt to understand or process those problems are similar. The music, the journals, the letters. The narrator is an extension of the most introspective parts of myself. Which aligns with my feeling that, at least at this point in time, the “voice” of a narrator I write can only be so different from my “voice”. Which takes us to the self-doubt thing (which we’ll revisit sometime). I don’t necessarily believe I can do something different. I don’t know if that is something that comes with more experience writing, or if there is a discomfort to reckon with in creating a narrator more different to me. I definitely found it hard (that is, doubted more the believability of what they were saying) writing some dialogue in the cry list, the brother in particular, when characters said things I would never say.

The main aspect that was autobiographical (and it’s less quantifiable): emotions. That minor unease when you sense the asymmetry between you and another person. The feeling that suddenly, listening to this piece of music in this moment, I am able to express a truth I could not before. And I suppose I am not saying anything new when I say that, subconsciously or consciously, we carry our feelings in the things we write. This story is no different. The cry list captures some of my emotions, houses them within a plot.

b. one story, several different stories?

It was only in the fourth chapter the cry list became self-referential with regard to main plot. Prior to that, there wasn’t explicit evidence it was all connected. This wasn’t really an issue in the same way the ‘is it fiction?’ question is, but it does underscore some particularities about this format.

A weekly newsletter is not the medium this story needed for expression. It keeps alluding to history that occurred earlier within itself, and it’s the same group of six people appearing on different beats. Knowing what happens earlier adds value for reading later. But presenting the story in a week-by-week format meant on occasion people (including me) forgot what had happened. There was an experience of reading a phrase and feeling “hmmm this connects to something earlier but I don’t know what” which maybe we don’t experience if the story is either: a) released all at once; or b) clearer?

There were two main advantages of doing the newsletter format:

a) getting out one to two and half thousand words a week was a sustainable rhythm. It meant I could write and/or edit a section each week with a finish point in mind.

Which reminds me: the fourth most asked question was some version of ‘how much did you have ready before the first release?’

- The first six letters were written last year. When I would review them before scheduling/posting I was almost entirely doing editing: tweaking word choices, grammar, phrasing, making sure details were consistent.

- But as we went on, two simultaneous threads ran:

- I had less and less written before it got to review time each week

- It became easier to generate new content/do the editing

So, for instance, chapters eight & nine were based on little outlines I had bouncing around for a couple weeks, but the text itself was majority written on the date that they were scheduled for “review”. This sort of rapidity of writing I didn’t imagine possible when I was editing the first chapter.

There was something about being in it every week. Having my head in the same story meant ideas about direction felt obvious at times. I grew more accustomed to the voice of the narrator, their tendencies, the way they might respond. Knowing that you were reading it, hearing little snippets of feedback, this offered me a clarity when making decisions which I would not have had if I were not conscious of who the audience was. There was something resembling flow.

But this rhythm didn’t give me much opportunity to do the kind of problem solving which time enables. Where you come back to something after not having seen it for a while and feel inspired.

An example of a problem: ‘Why is the narrator wearing a hoodie?’ in chapter three. When the first chapters of the cry list released it was Summer in Australia, and this part of the story did feel like it was occurring in Summer. However it was important for the narrator to be wearing a hoodie when finding the cry list, because this meant the narrator could clearly hide it from the father. So I “solved” that by adding the dad blasting the a/c in a previous chapter, and it was a moment where everything made sense: this dad would blast the a/c, this narrator would be wearing a hoodie during these family moments.

Problems felt less solvable as I had less and less time to solve them. I would have loved to tease out ‘why does the narrator not say anything on the way home from the concert about her giving up the secret?’ in chapter ten. So I think this writing lots every week led to a lack of polish, and maybe a lack of depth on later letters. (It’s also true that the chapter ten problem is a more difficult problem to ‘solve’ than the chapter three one. I suppose it just takes time to embody a different perspective to ours - this is never an automatic thing, even when the different perspective is a neighbour to our own.)

c. uhhh how long is this project?

I had also not communicated specifically the story would be as long as it was. Most pieces I have written in the last year were between one and five thousand words. The cry list was many times that. Moreover, fourteen weeks felt long from my perspective - not for the story but for this format. It’s so hard to take everything in (sometimes anything) when we sit down to read a book for fifty minutes (roughly half as long as it would take to read the cry list from start to finish), or when we cook whilst listening to a podcast, or when we try to listen to our friends share a few anecdotes. How much can we hold onto when we spread that time across fourteen weeks? Maybe I could have made some of the chapters more self-contained, so that each week felt less like a jigsaw piece and more like a room of a house? I would be interested in hearing from people who joined part-way through how accessible the letters felt when you read them out of order, and just generally if people felt lost at times?

Although, part of the reason it was unexpectedly long relates to the second most asked question: did I know the end at the start?

I see fiction as less a roller coaster (you know where you’re going to end, and it’s kind of back at the start) and more like arriving at a friend’s house without knowing what the plan is. You may very well end up back at their house, or even stay there the whole time, but you don’t know that this will be the case, you only know enough (you have a certain amount of time to hang, you want to spend time with your friend, the fact that it’s this friendship opens it up to certain possibilities and not others, etc.) to roll with it, and this infuses the hang out with a satisfying unclarity, or more generously worded, with openness.

Which is to say I didn’t know the ending. Not only in terms of plot. I didn’t know what the story was “saying about” gossip when I started out, and I only realised many letters in the complexity of the relationship between the narrator’s withdrawal of information and their family’s use of information. So in the themes, in the softening of the narrator towards their family, I didn’t always know where it would go.

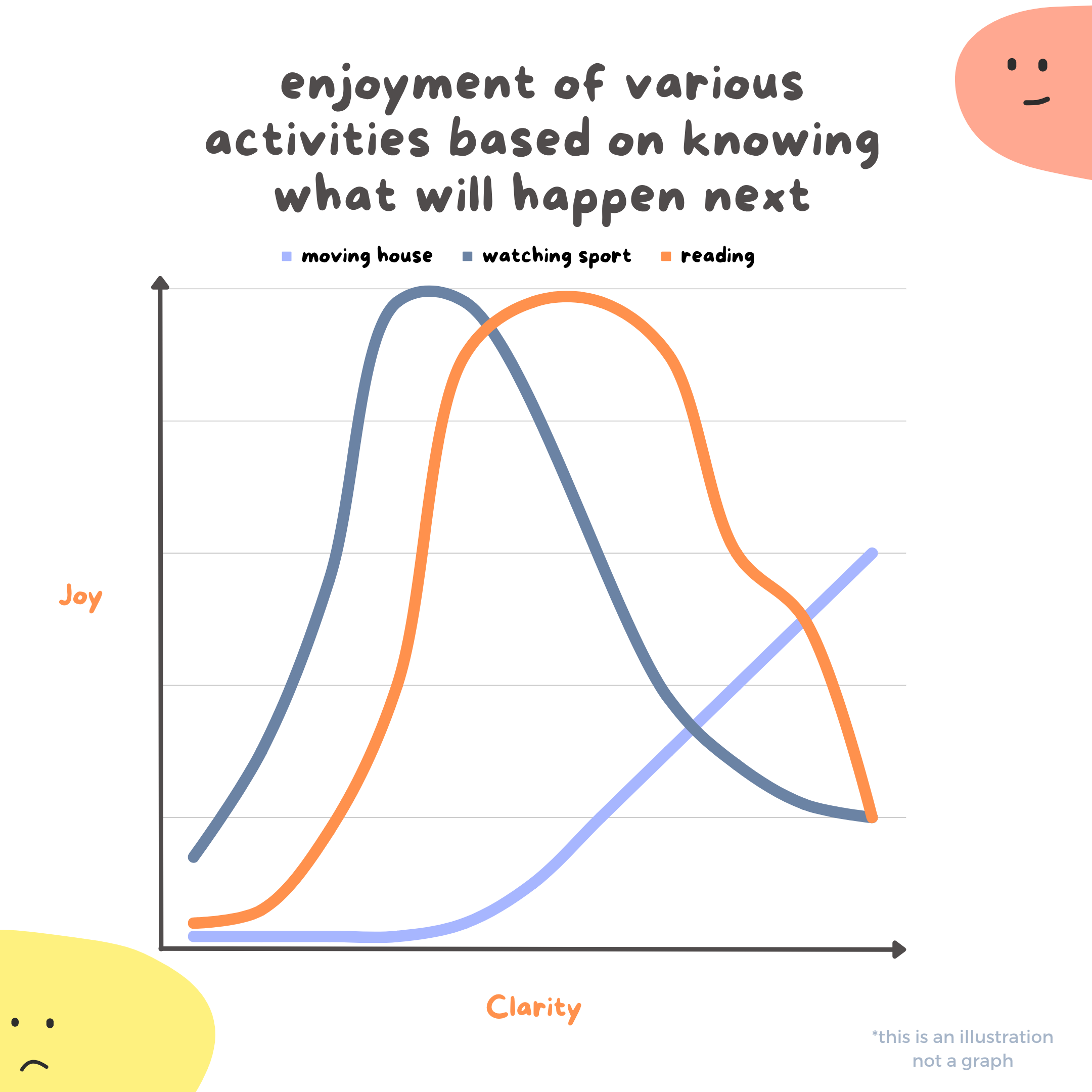

a graph

Reflecting on this, I sketched a “graph”. Essentially it’s suggesting that depending on the activity, our enjoyment is mediated by how much we know what is going to happen next (which I have labelled ‘Clarity’). There is a certain amount information you need (the threshold of sense I mentioned in the last letter), a narrowing of possibilities which enables enjoyment (e.g. understanding the rules of a sport, being able to understand a character’s motivations in a novel). But there is a point at which you can know “too much” (most blowouts in sports are uncompelling, there is an evaporation of tension when it becomes obvious the protagonist in a story won’t lose anything meaningful, that feeling of sadness when a thing is finished).

Of course there is so much context here the graph doesn’t highlight. There are changes as the story proceeds: we have more tolerance at the beginning for not knowing, and less tolerance at the end. Different genre conventions and twists change the availability of information. Particular characters or voices in stories might mean we are along for the ride even if we have no idea. Our personalities impact our comfort with uncertainty: I don’t mind as much not knowing what’s going on, even when moving. Etc.

And to be clear: stories are about specific things, contexts, people. If a story is about someone running late, our feelings as readers are dependent on whether they are the-person-in-that-friend-group-that-is-always-late-even-after-that-time-etc., or if they are someone who has never been late for the same cup of tea they have with their sibling every Tuesday after work and suddenly is. We need that narrowing of possibilities to feel we are in a story rather than a general or random account of human behaviour. We ask different questions, and different answers will make us feel we have spent our time reading well depending on the specifics we know.

But the joy of reading relies on the tension that comes from this knowing but also not knowing. Just as a crucial element of sport is not knowing who is going to win. And I think this is true for the writer as well as the reader. There is a sense in which I was happiest with the Cry List when I didn’t know exactly how it was going to turn out.

But then maybe also as fundamental to a story is that it ends at some point? Unsurprisingly, another unfinished thought.

a survey

I didn’t mention earlier the second advantage of doing the story as newsletter format:

b) I had the joy of hearing from different readers every week : )

Here is the reader survey. If you’ve got a little time, share your experience of the cry list and have some input on the future of this newsletter. No question or comment is unwelcome.

Back next week with some thoughts on self-doubt, and the themes (hopefully on Wednesday this time).

: )